The famed pious headmaster, Thomas Arnold, “who had long had his eye on Flashman, arranged for his withdrawal next morning.”

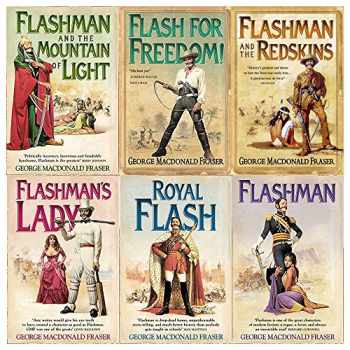

Hughes introduces Flashman simply as “Flashman the School-house bully,” who likes to organize tossing the smaller boys at Rugby School in a blanket: “What your real bully likes in tossing, is when the boys kick and struggle, or hold on to one side of the blanket, and so get pitched bodily on to the floor it’s no fun to him when no one is hurt or frightened.” Hughes is at pains to explain that “bullies are cowards, and one coward makes many,” but, beyond that, he is so little interested in Flashman that he dismisses him in a paragraph, halfway through the book, for getting “beastly drunk” on gin punch amply overlaid by beer. It was a brilliant stroke of Fraser’s, in the first volume, “Flashman” (1969), to retrieve a minor figure in Thomas Hughes’s greatly popular, intensely Christian best-seller “Tom Brown’s School Days” (1857) and reanimate him as a lauded though inadvertent hero in the service of the British Empire.

He has written other fiction, plus history, autobiography, and film scripts, besides serving as Flashman’s assiduous editor the series is presented, under the over-all title “The Flashman Papers,” as its protagonist’s memoirs, which need only a few footnotes and spelling corrections to become excellent entertainments. Fraser, an Englishman schooled in Scotland, served with the Highland Regiment in India, Africa, and the Middle East, before settling on the Isle of Man. “Flashman on the March” (Knopf $24), George MacDonald Fraser’s twelfth book about the Victorian rogue and soldier Flashman, finds both the author and the hero in dauntless fettle, the former as keen to invent perils and seducible women as the latter is, respectively, to survive and to seduce them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)